Looking Back: Hogan's 'Triple Crown' Season of 1953

As the calendar turned to 1953, questions arose about whether Ben Hogan was finished. The Fort Worth, Texas, man was coming off a rather pedestrian 1952 season after making waves in 1950 and 1951.

In 1952, Hogan won a single tournament - the Colonial Invitational in his native Fort Worth. While he finished tied for seventh in The Masters and third in the U.S. Open – both title defenses – many characterized his season as a failure. Couple that with a younger generation led by Cary Middlecoff and Jack Burke Jr., who were winning with more regularity, and Hogan’s main rivals, Sam Snead and Lloyd Mangrum, who continued their winning ways. After everything he’d been through, including a near-fatal automobile accident in 1949, maybe Hogan was actually finished?

Of course, Ben Hogan believed otherwise.

While his 1952 season was disastrous in his eyes, he still had the drive to prove that he was the best golfer in the world. That offseason, he took a club pro job in Palm Springs, Calif., where he spent the winter honing his game on the driving range, cementing his legacy as the man that created modern golf practice. He hit more than a thousand balls each day, re-perfecting his iconic swing to make one last run at immortality.

While his swing was primed for the season, Hogan made waves early on by making a huge equipment change – he changed his golf ball. Explored flawlessly in James Dodson’s Ben Hogan: An American Life, Hogan was approached by legendary MacGregor representative Toney Penna at an early season event and asked if he would continue to play the company’s “Tourney” golf ball. Hogan unceremoniously told Penna, “Hell no! It’s the worst golf ball ever made.” The MacGregor balls were notoriously subpar and as long-time MacGregor player Mike Souchak noted in Dodson’s book, “You were lucky to get two or three balls in a dozen that were playable, and they were often ‘out of round’ after a hole or two.” Hogan’s ball switch ultimately led to his divorce from MacGregor altogether by season’s end.

Hogan arrived at Augusta National determined to show MacGregor and the world that the Hogan of old was back with a vengeance. With a Titleist ball in play, Hogan proceeded to dominate the 1953 Masters, winning by five shots over Ed “Porky” Oliver and eight shots over Lloyd Mangrum. Hogan was back.

A few weeks later, he continued his dominant play. Despite a final-round 74, Hogan won the Pan American Open in Mexico City by three shots over Dame Douglas and Fred Haas. A couple of weeks later, he successfully defended his title at the Colonial Invitational, defeating Middlecoff and Doug Ford by five strokes. Hogan had won three of the four events he’d entered and was primed to add another U.S. Open title at Oakmont in June.

Ben and Valerie Hogan arrived in Pittsburgh a week before the U.S. Open qualifying was set to begin. Back then, only the defending champion had a guaranteed spot in the field. The three-time U.S. Open champion hoped to get a few practice rounds in at both the championship host site – Oakmont Country Club – and at the other qualifying site, the nearby Pittsburgh Field Club. Among 300 other hopefuls, Hogan successfully claimed one of the 155 available spots in the 1953 U.S. Open field. He shot a 5-over 77 at Oakmont and followed that up with a 2 over 73 at the Pittsburgh Field Club. With his spot solidified, his true preparations began.

But while Hogan was trying to solve the Oakmont puzzle, a portion of the field was threatening to boycott the championship because of the course’s bunkers. Since its inception, Oakmont had been known for its treacherous “furrowed” bunkers. The hazards were filled with river sand from the nearby Allegheny River, and raked perpendicular to the hole with a rake referred to as the “Devil’s Backscratcher.” This rake featured four-inch steel tines that created deep “furrows” in the sand that forced any player who found their ball there to have to pitch out sideways to avoid further damage.

The players, with some sources pointing to Lloyd Mangrum as the ringleader, believed the furrows were unfair. They made their stance clear: change the raking or we don’t play. The USGA, Oakmont and the players eventually came to an agreement -- the fairway bunkers were raked like bunkers on a normal tour stop, while the furrows remained around the greenside bunkers. It was a compromise that both the players and club were not fully sold on, but it ended the potential boycott and got the competition started.

While the furrows saga unfolded, Ben Hogan was diligently at work on the golf course. Followed by The New York Times’ Arthur Daley, Hogan played practice rounds by hitting three balls off each tee and playing in from there. Daley was shocked to find Hogan so open in these rounds, discussing strategy with the scribe and stating that he [Hogan] believed the par-4 17th hole would “make-or-break” the eventual champion.

On the eve of the championship, the media gathered around Hogan’s locker on the second floor of the Oakmont clubhouse to ask him a variety of questions about the competition. A legend around the club exists about this media scrum, involving fabled golf writer Herbert Warren Wind, then of The New Yorker. Wind supposedly asked Hogan how he planned to traverse all of the course’s treacherous ditches and bunkers during the event. Hogan reportedly stated to Wind that he “didn’t plan on being in them.” When Wind followed up by asking Hogan his overall strategy to win the Open, Hogan supposedly retorted, “To shoot the lowest score, Herb.”

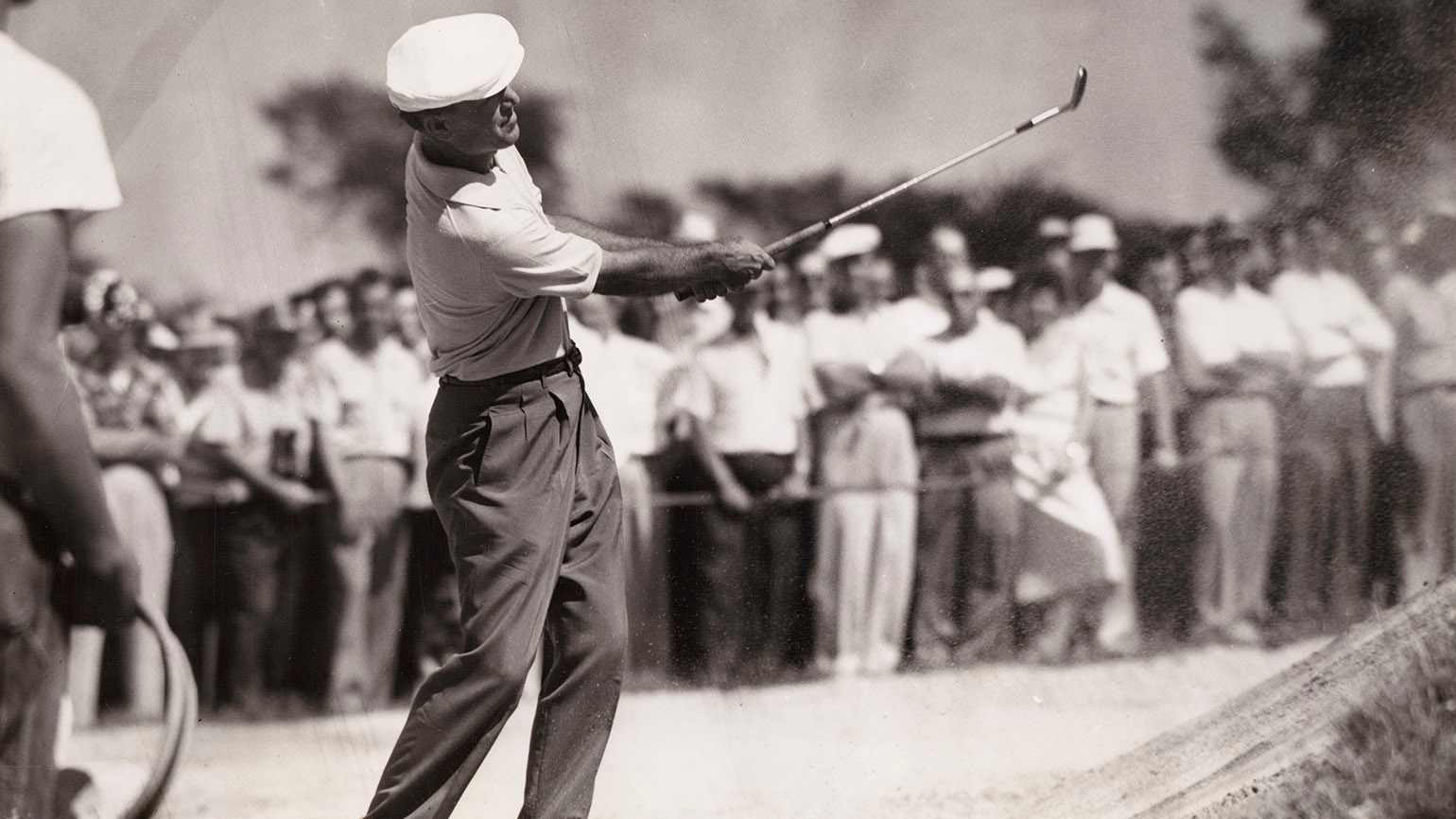

As it turned out, Hogan’s blunt statement proved prophetic. The next morning, teeing off into a dense fog that would have delayed play in modern times, Hogan methodically traversed the golf course and shot the championship course record in the process. He hit all 14 fairways en route to a 5-under 67. The Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph asked Hogan about his round and if Oakmont put him on the defense in the same way Merion or Oakland Hills did (site of his 1950 and 1951 U.S. Open triumphs, respectively). He responded, “Well, you can’t attack Oakmont. If you try to fight it, you’ll get more double bogeys than birdies.”

The difficult Oakmont course provided lower scores than expected in the opening round. Besides Hogan, five other players broke par, including Oakmont member and former member of the 1937 University of Pittsburgh national champion football team Frank Souchak, who fired a 2-under 70 to sit in a tie for second.

The one player besides Hogan that many believed could capture the Open crown was long-time U.S. Open bridesmaid, Sam Snead. Despite three prior U.S. Open runner-up finishes, Snead was playing solid golf after an opening-round 72. He also had experience at Oakmont, having won the PGA Championship there in 1951.

Snead made his presence felt in the second round, when he fired a 3under 69 to trail Hogan, who fired an even-par 72 in Round 2, by two shots after 36 holes. Despite his pre-championship complaints, Lloyd Mangrum also entered the conversation, shooting a 2-under 70.

One player who struggled at this Open was a local boy from Latrobe by the name of Arnold Palmer. Recently discharged from the U.S. Coast Guard, Palmer shot 84-78 to miss the cut by nine shots. Though disappointed, he went on to play in five total U.S. Opens at Oakmont, nearly winning the 1962 and 1973 championships, losing an 18-hole playoff in the former to Jack Nicklaus.

As was custom in this era, the final two rounds of the U.S. Open were played in one day. (The USGA changed to a four-day format in 1965.) This format always raised questions in regards to Hogan, who just four years earlier had nearly died in a car accident in west Texas. Hogan, who suffered a fractured pelvis, ankle, and collarbone, developed blood clots that required surgery that tied off his vena cava in his legs. Because of this, Hogan had pain and difficulty walking for the remainder of his life, and the grind of a 36-hole day proved to be a true Herculean effort for him.

After the morning third round, it was clear the title was a two-horse race between Hogan and Snead. The duo were five shots clear of third place. Snead shot another even-par 72 in the third round, while Hogan struggled to a 1-over 73. Hogan retained a one-shot lead over Snead heading into the final round.

Hogan teed off a few groups ahead of Snead and by the turn, they were still neck-and-neck. Hogan carded a 1-over 38 on the front, just as Snead would about 45 minutes later. Hogan made his first birdie on the back nine at the par-3 13th. He nearly birdied the 14th too, settling for a par when his putt just slid past the hole. Hogan then bogeyed the 15th hole, which he later characterized as “the most demanding hole I’ve ever played,” before a par at the 16th.

A few groups behind him, Snead’s attempt to catch his rival was thwarted by a balky putter. He three-putted for double bogey on the par-5 12th and failed to convert par putts on the 15th and 16th holes. Feeling his chance of winning slipping away, his heart was once again broken when he heard deafening roars from the 17th green.

As Hogan had told Arthur Daley, the 17th proved to be the pivotal hole. Knowing he had a lead, Hogan played daringly -- he attempted to drive the green. He lined up his drive and sent his patented fade right to the opening of the green and gave himself an eagle chance. The gallery roared as he proceeded to two-putt for birdie. He finished off his round with another superb shot, this time a 5-iron to 10 feet on the 72nd hole. He made the putt for a 3-under 32 on the inward nine and a 1-under 71.

Snead parred his final two holes to post a disappointing 5-over 76. He finished a bridesmaid once again, this time six shots behind Hogan. He would never claim a U.S. Open title, and his four career runner-up finishes has only been surpassed by Phil Mickelson’s six. Like Snead, Mickelson has never raised the trophy. Lloyd Mangrum was third, nine behind his fellow Texan.

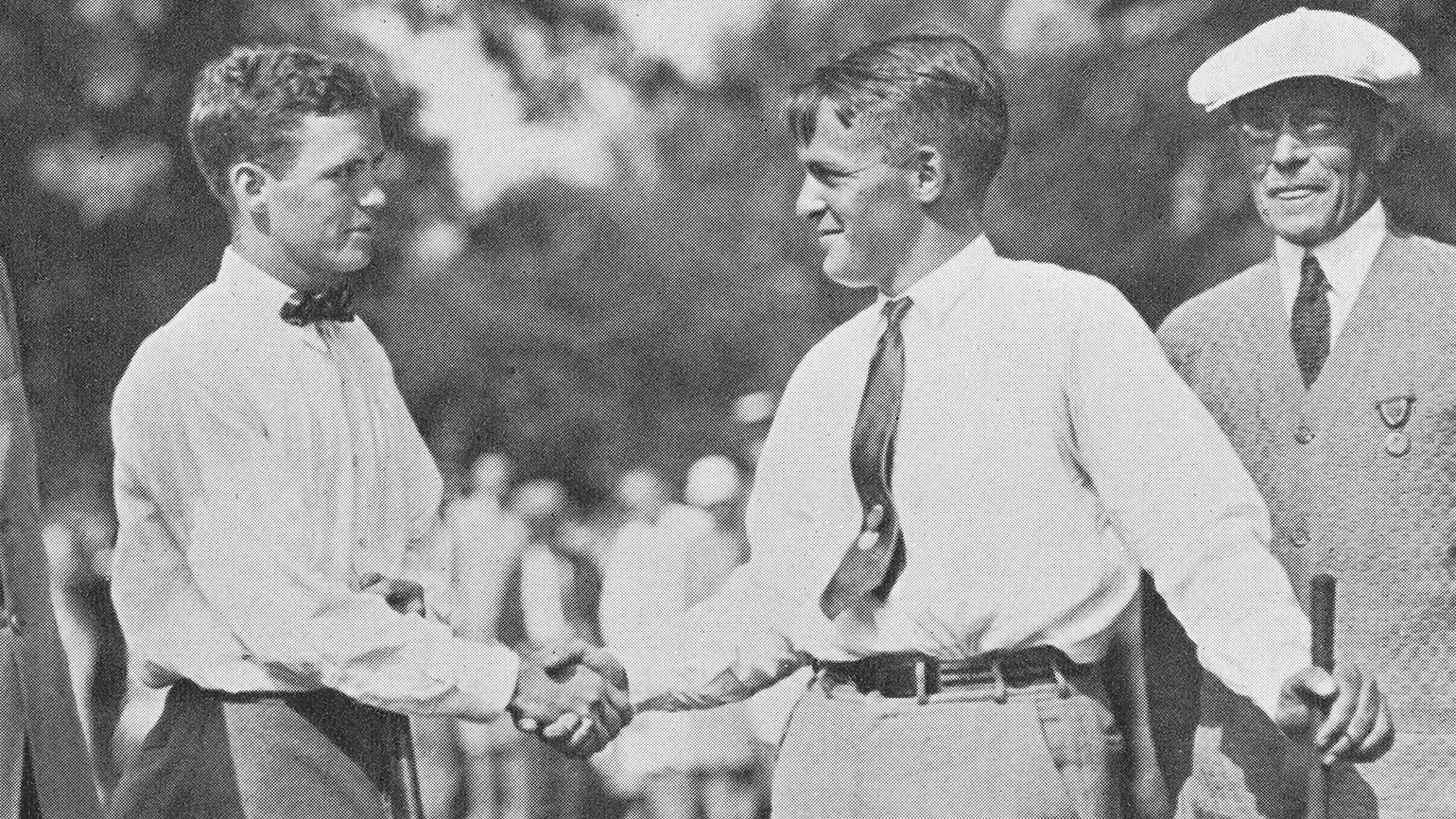

Hogan’s triumphant victory at Oakmont made history. He joined Willie Anderson and Bob Jones as the only four-time champions in the event’s history. They would later be joined by Jack Nicklaus in 1980. His 5-under, 283 was also the lowest winning score in the three U.S. Opens at Oakmont to date.

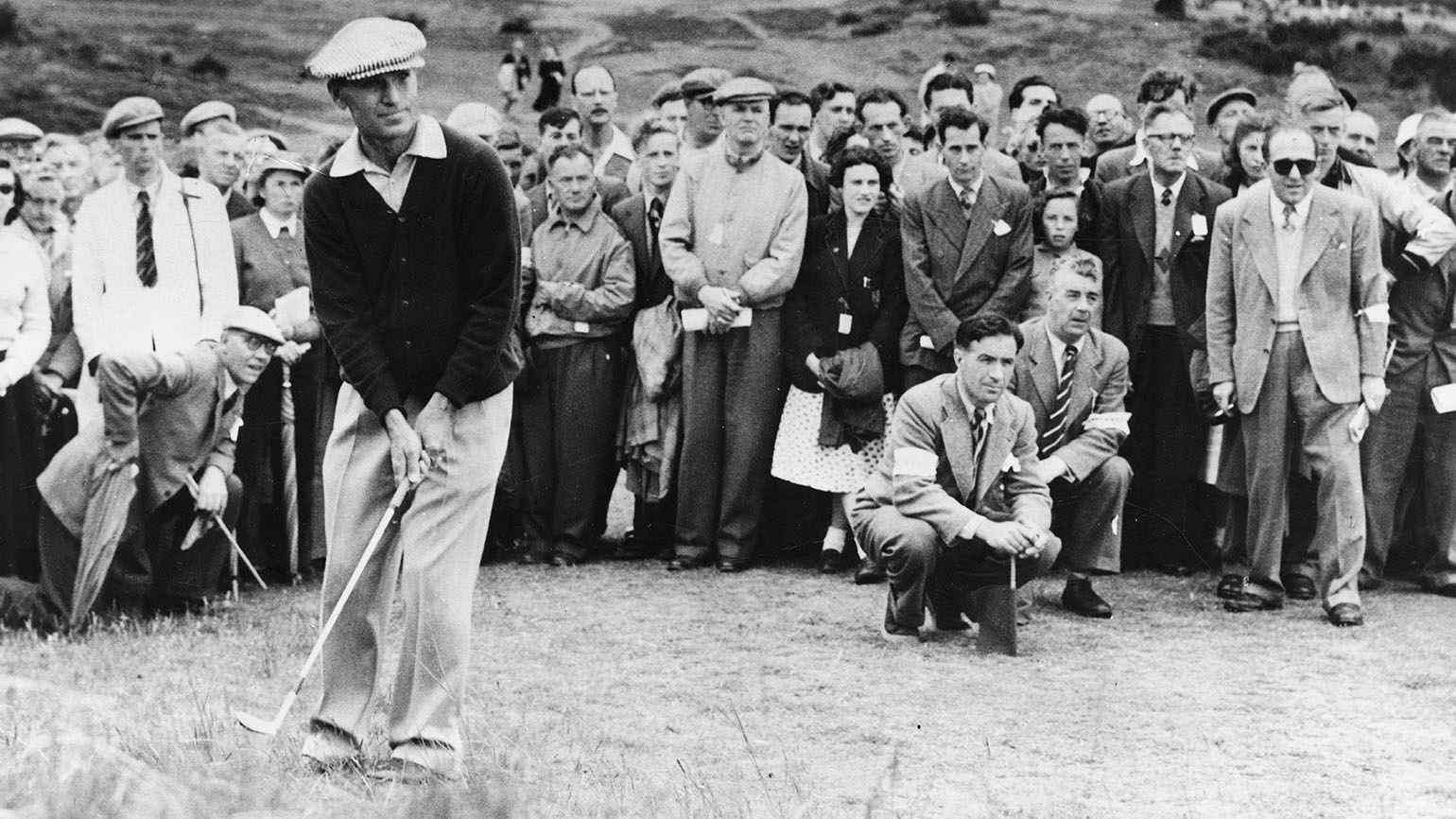

Following his victory, Hogan made his lone sojourn across the Atlantic to compete in the Open Championship. At difficult Carnoustie, Hogan shot played 6-under golf over the final 36 holes to claim the Claret Jug by four shots over Peter Thomson, Dai Rees, Antonio Cerda and amateur Frank Stranahan. It was Hogan’s third consecutive major victory of the season, one away from the modern single-season Grand Slam of the Masters, U.S. Open, Open Championship and PGA Championship. Jones won the Grand Slam in 1930 with his victories in the U.S. Open, U.S. Amateur, British Open and British Amateur.

Disappointingly, Hogan would not claim the Grand Slam in 1953. Many ask what happened at the PGA Championship that kept him from immortality. The answer is simple: he didn’t participate. In this era, it was uncommon for Americans to make the trans-Atlantic journey that Hogan made in 1953 to participate in the Open Championship. Because of this, there was no coordination in scheduling between The R&A and the PGA of America, who both scheduled their biggest event for the same week. So Hogan had to choose, and because of the demanding Match-play format of the PGA Championship in this era, Hogan ultimately decided to try for the Claret Jug. If the schedule had been different, could Hogan have completed the Grand Slam? We will never know.

Even without the PGA title, Hogan completed arguably the most impressive professional season in American golf history to that point. Regarded as the “Triple Crown” season, Hogan became the first professional to win three majors in a single season. The feat has only been matched once since when Tiger Woods, in 2000, won the U.S. Open at Pebble Beach, the Open Championship at the Old Course in St. Andrews and the PGA Championship at Valhalla. He would win the 2001 Masters to hold all four major titles at one time.

The 1953 season also proved to be Hogan’s final hurrah. Hogan had a few more solid chances in majors in the coming years, especially in the U.S. Open, but he’d never win another.

He finished tied for sixth in his title defense at Baltusrol in 1954 and heartbreakingly lost to Jack Fleck in an 18-hole playoff playoff at The Olympic Club in 1955. He finished tied for second again in 1956 at Oak Hill and held a share of the lead going into the 71st hole at Cherry Hills in 1960 before letting that one slip away to Arnold Palmer. Hogan won only one more PGA Tour event after the 1953 Open Championship: the 1959 Colonial Invitational.

After the 1953 season, Hogan cut back his playing schedule even further, typically only appearing at the majors. He spent all his time building the Ben Hogan Golf Company, manufacturing precision clubs made to Hogan’s insanely high standards. When he wasn’t at the office, he spent his days at Colonial Country Club and Shady Oaks, where he continued to play and practice for the remainder of his life. William Ben Hogan passed away on July 25, 1997 at the age of 84 in Fort Worth, Texas, a 64-time PGA Tour winner and nine-time major champion.

David Moore is a golf historian and author who serves as the Curator of Collections at Oakmont Country Club, the site of the 125th United States Open. David is co-author of “Battling the Church Pews: The History of Golf’s Premier Events in Western Pennsylvania” and his writings have appeared in The Golfer’s Journal and The Golf: The Journal of the Golf Heritage Society.