Whose Course Is It, Anyway? Thomas Built Upon Fowler’s Vision

When Gil Hanse met with the leadership of The Los Angeles Country Club in 2005, he very much wanted to land the club’s proposed restoration project for his fledgling course design firm. But he also wanted to make one thing clear.

“I remember sitting in the interview room and saying, ‘If George Thomas isn’t your architect, then we’re not your architect,’” said Hanse. “We didn’t want to be involved in making alterations to his design. That resonated with some people on the committee, and we were brought on board.”

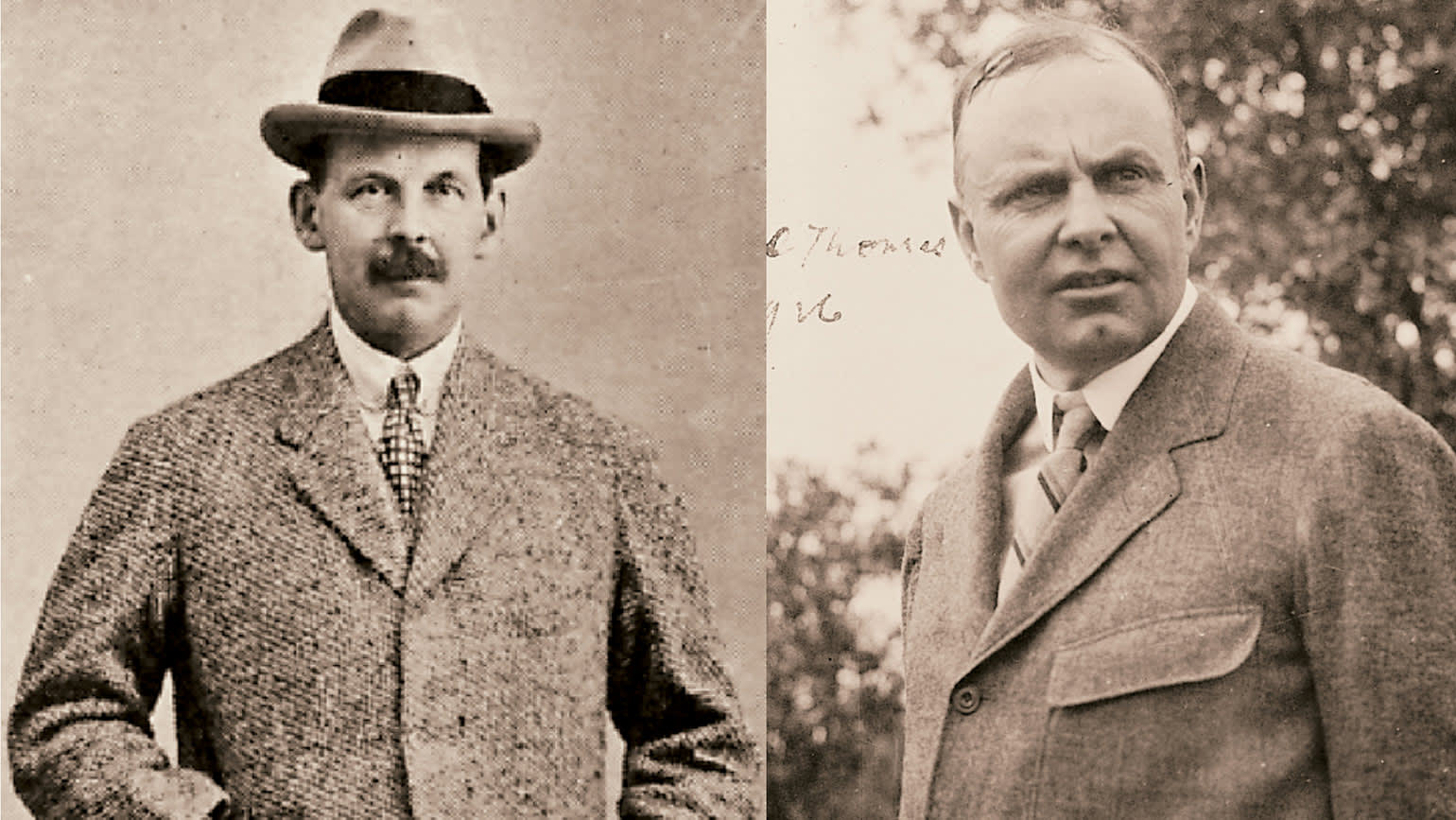

But George C. Thomas Jr., who is renowned for designing nearby Riviera and Bel-Air Country Clubs as well as LACC’s North Course, isn’t the only Golden Age architect affiliated with the layout that will host the 123rd U.S. Open Championship in June. In fact, Thomas helped to bring another designer’s vision to fruition before taking the reins himself.

The history of the club spans 126 years, with three sites preceding the current property bordering Beverly Hills, where several members laid out an 18-hole course that opened in 1911. Before the decade was out, the club had grown to 500 members, and club leaders wanted to improve upon the existing layout. They also purchased 150 adjacent acres so they could expand the offerings to 36 holes.

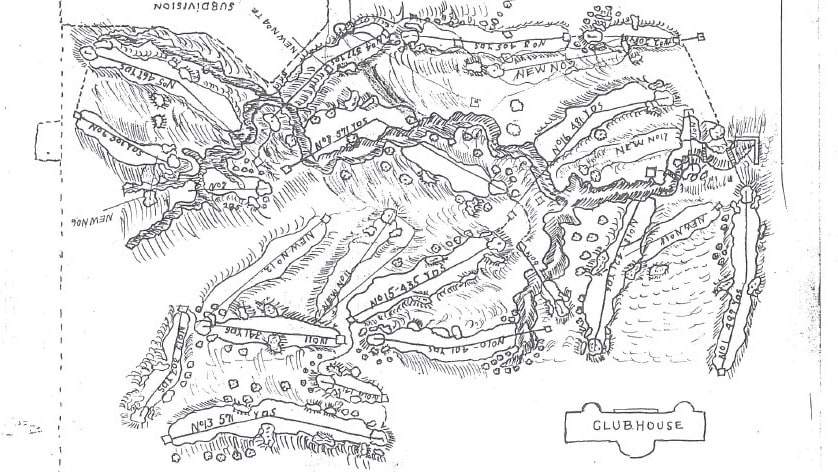

The club hired W. Herbert Fowler, an English architect who is best known for designing Walton Heath in England and Eastward Ho! on Cape Cod, as well as the concept for the 18th hole at Pebble Beach. Fowler visited LACC on two occasions and provided drawings as well as plasticene models of each hole and its typography – considered cutting edge for the time. His designs for the North and South courses were presented to Thomas, a recent transplant to Los Angeles who supervised the construction.

The Fowler-designed North Course debuted on Aug. 10, 1921, and it was seen as a vast improvement over the “Beverly Course,” as the 1911 layout built by members had come to be known. When LACC hosted the first Los Angeles Open in January 1926, some of the professional golfers voiced their displeasure with the layout, and Thomas was enlisted to make some alterations. William P. “Billy” Bell, a former superintendent with whom Thomas had first collaborated in 1925 on the La Cumbre Country Club in Santa Barbara, was hired to supervise the construction.

“Fowler believed in playing the contours of the land,” said Adrian Whited, LACC’s historian and a 53-year member. “Fowler had pretty good ideas of how to get from A to B. Thomas improved on those applicable routings with the knowledge he had picked up designing Riviera, Bel-Air and Ojai Country Club in the intervening years.”

The tweaks to Fowler’s North Course began with the implementation of a bunker style that Bell and Thomas, who hailed from the so-called Philadelphia school of course design that produced Pine Valley and Merion, had adopted in their efforts at Riviera and Bel-Air.

“Thomas was this charismatic, fascinating man who lived an incredible life in his short time,” said Geoff Shackelford, author of the 1997 book, “The Captain: George C. Thomas Jr. and His Golf Architecture.” “He got his nickname from being a pilot in World War I, and his diverse interests included rose hybridizing, deep sea fishing and dog breeding.” In fact, Thomas built a 20-acre estate behind the nearby Beverly Hills Hotel because he found the climate ideal for rose cultivation.

“By 1927, when Thomas came back with Billy Bell, there were tremendous strides in golf course design, both in equipment available to them and in terms of philosophy,” said Shackelford, who worked as a consultant with Hanse on the LACC restoration. “Bell was a burgeoning architect and an innovator, and with each project you could see they got more creative with the bunkering they were doing.”

The USGA’s Jeff Hall, who will help to set up the course for the U.S. Open, said, “The bunkers have a natural ruggedness that really fits my eye, as well as a bit of unpredictability. You could have a relatively straightforward shot, or you could be in one of the little nooks in the bunker and the ball might be sitting OK, but how do you take a stance? You could also get stuck in the fescue that makes up the surrounds of the bunker and have a very difficult shot.”

Make no mistake – along with the innovation and efforts to improve the course, there were egos involved, as detailed in the club’s centennial book, “Links With a Past: The First 100 Years of The Los Angeles Country Club.” Thomas clashed with club founder Joseph Sartori, at one point complaining, “Our test of golf is below average in this district.” When his request for a parcel of land to create a new tee was rejected, Thomas wrote, “I do not wish to dictate the club’s policy, but on the other hand, must ask you to excuse me from building any course which I do not think has sufficient merit. I am only interested as I can produce a superlative course.”

The club acceded to Thomas’ will. “After a few tweaks by Thomas and Bell, the club said, why don’t we just let you have the entire golf course,” said Hanse. “What you see now, there are still some components of Fowler’s original design in the routing, but all of the complexes – both bunkers and greens – and a significant number of the holes were rerouted to Thomas’ design, so that’s why he deserves the lion’s share of the credit for the North.”

Exactly how much credit is still debated by those close to the restoration project and the club’s history.

“There's almost nothing of Herbert Fowler left today,” said Shackelford. “We have a lot of evidence, including aerial photos. Thomas essentially created six entirely new holes and 12 holes that were in the original Fowler routing, but he blew up everything – the style went from a very geometric style to more strategic, where the golfer could use the ground to funnel the ball in. It was kind of the end of the penal era of architecture.”

Whited estimates that “Ten or 11 of today's holes on the North are the same basic routing that Fowler did, and I think he deserves a lot more credit. Fowler has been somewhat forgotten.”

Not completely. Final qualifying for the U.S. Open returns to England this year for the first time since COVID-19 halted the process in 2020. On May 16, the 36-hole test to make it into the field at LACC will take place over a pair of acclaimed Fowler designs, the Old and New Courses at Walton Heath, in Surrey, England.

Ron Driscoll is the senior manager of editorial services for the USGA. Email him at rdriscoll@usga.org.